Routing in VIPER Architecture

Introduction

The primary function of a Router is to manage the display of a group of scenes, implemented by ViewControllers, using a pattern such as stacking, direct access or serial access.

The iOS UIKit architecture offers variety of routing ViewControllers for managing scene transitions, such as Navigation, SplitView, and TabBar. In iOS architecture, it is the responsibility of a child ViewController to manage a scene transition by referencing its parent (routing) ViewController. This tightly couples the child ViewController to its parent and siblings, making it complicated to use it in multiple situations. This architecture causes the child ViewController to become bloated with routing code that should be placed in the parent controller.

In the VIPER architecture, a parent ViewController, known as a Router, is fully responsible for the management of its child ViewControllers. This effectively decouples ViewControllers from one another.

A VIPER architected Router ensures that its child ViewControllers are independent of their parent or sibling ViewControllers. This means that a ViewController which is part of a sequence managed by a NavigationController may also be presented in a SplitView or in a modal popup.

A secondary function of a VIPER Router is to maintain local system state for its child modules.

This article is a continuation of the article A Crash Course on the VIPER Architecture. An app which demonstrates the VIPER architecture with examples of both custom and stock Routers can be found at Todo.

Routing in VIPER

In VIPER, although a child ViewController asks for a scene change, the management of the scene change is the responsibility of the parent. The parent is known as a Router.

In iOS, a ViewController is given access to its parent via one of the Navigation-, TabBar- or SplitViewController properties. Knowledge of the parent is required because it is the parent that knows how to present a new controller or to set up a navigationBar.

Allowing this kind of access means that the child knows about and can directly control the behaviour of its parent. This circular relationship causes dependency problems, since the added responsibility ties the child to a predetermined environment defined by presentation-style or system state. Normally, this kind of relationship would be seen as a code smell and would never be allowed upon review - but somehow it lingers.

The dependency problem is most obvious when you try to use a ViewController in the context of supporting a small iPhone, a large iPhone and an iPad. Depending on the device and the orientation, the ViewController has to be parented by either a NavigationController or a SplitViewController. iOS tries to fix the problem of using a ViewController in this circumstance by having us use the show(:sender:) and showDetail(:sender:) methods to remove the need for the child to know which type of container it is in - but this is a special case for those 2 controller types.

In VIPER, the code for ViewController presentation is moved to the parent ViewController. A VIPER architected child ViewController makes no assumption about its environment and, as such, is available for use in any role, whether defined by presentation-style or system state. The child simply requests that routing is required. This is the same pattern as found in the Android architecture, where Activities perform routing for Fragments.

A VIPER Router is implemented just like a regular VIP module. A Routing ViewController may be inherited from a Navigation-, TabBar-, or a SplitViewController, as usual.

Custom routers can be created by inheriting from a plain ViewController. A custom router can implement non-standard usage patterns such as menus, paging, or some other domain-defined sequence.

Each VIPER Router has a ViewController and a Presenter, and occasionally, a UseCase. The main difference between a routing VIP-module and a regular VIP-module is that its ViewController displays child ViewControllers instead of just views, although some might display both.

A ViewController’s Presenter Communicates with the Router

An important rule of VIPER is that any event received by a ViewController must be forwarded directly to its Presenter, without further processing. The Presenter forwards the event to the module’s Router. A ViewController does not pass events directly to its parent Router. The router injects itself into its child Presenters.

The Router’s VIP Stack

A router has its own VIP stack: A ViewController, a Presenter and a UseCase. In order to understand how to implement a Router it is helpful to understand the implementation of a custom Router.

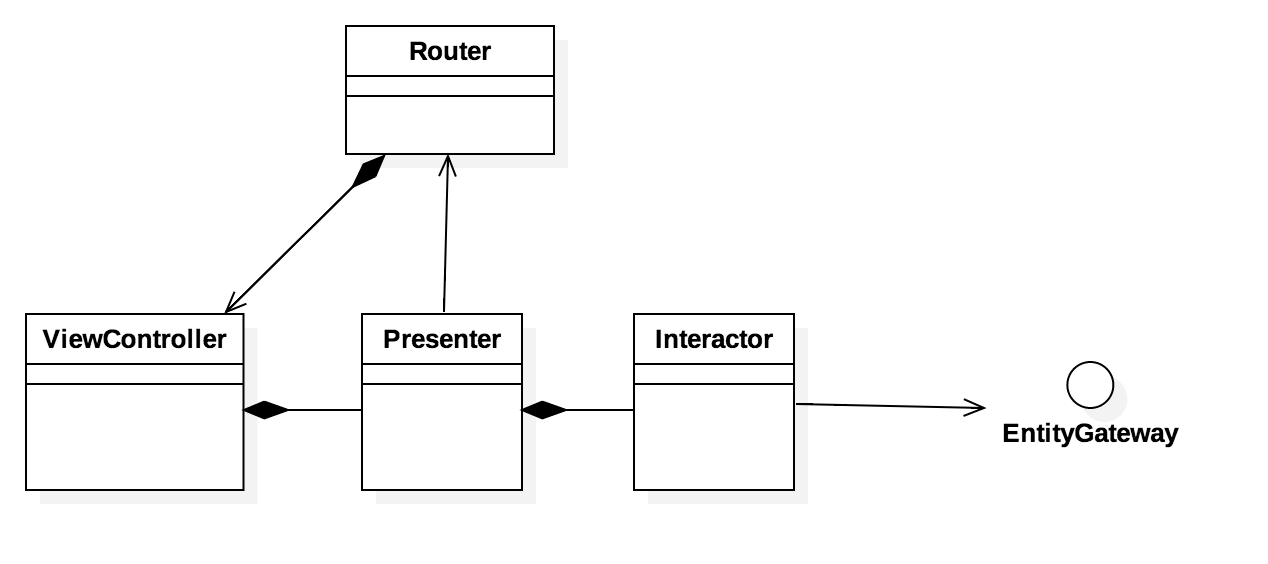

Here is a diagram of a VIP-stack:

In the diagram, you can see that the Presenter communicates with the Router. As far as the child VIP-Stack is concerned, the Router is a black box - it does not matter that the Router is actually another VIP-stack.

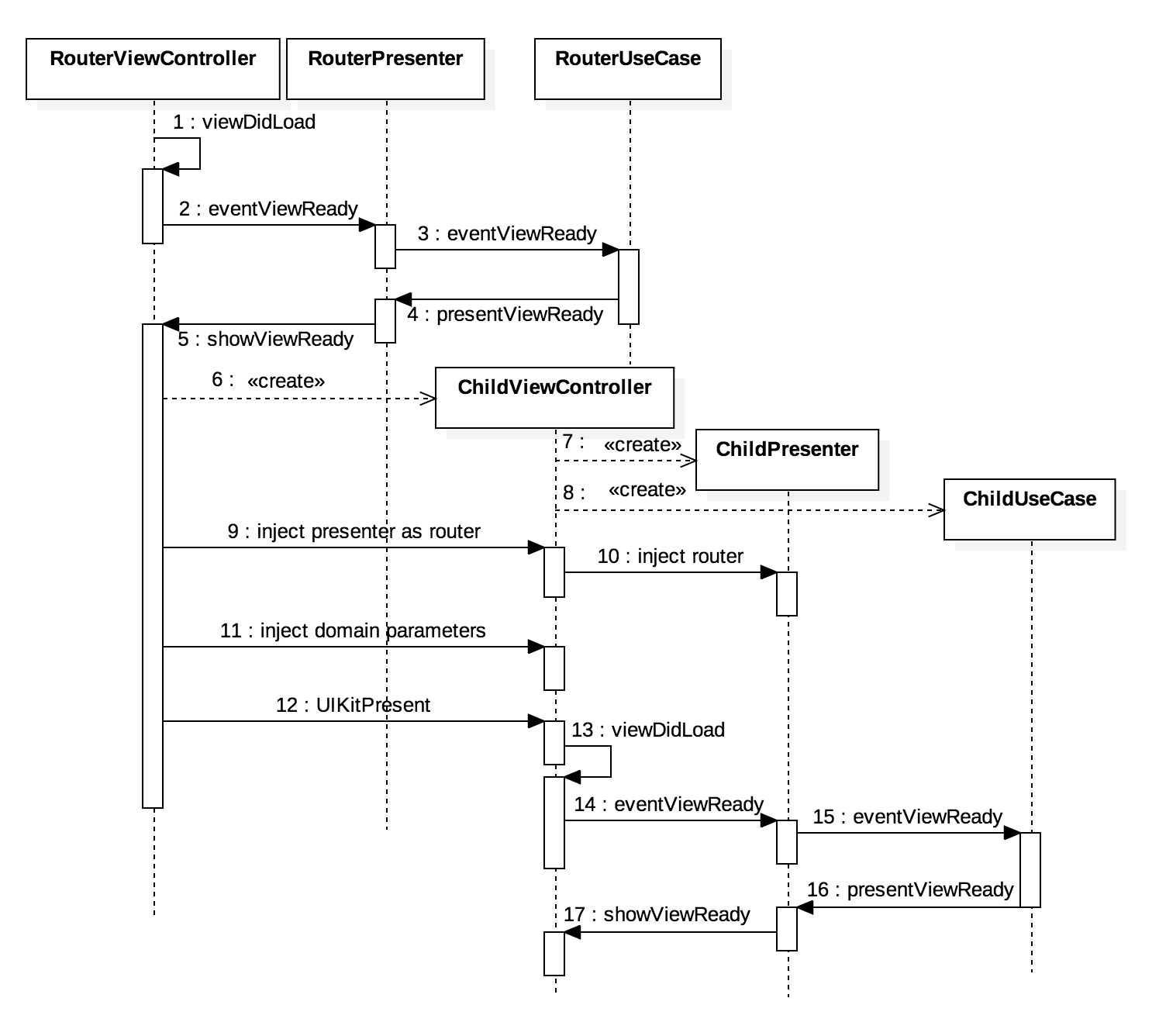

Here is a diagram that details the interactions between a parent VIP Router when presenting its initial child:

The ViewController

The role of a Router’s ViewController class is the same as it would be without VIPER: to perform the work of changing scenes.

A custom Router (a UIKit container ViewController) sends all of the events that it receives, including lifecycle events, to the Presenter. The viewDidLoad is implemented as it would be in any other VIP module:

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

presenter.eventViewReady()

}

Here is an example of a ViewController forwarding a Cancel event to its Presenter:

class ItemEditViewController: UIViewController {

...

@IBAction func cancelTapped(_ sender: UIBarButtonItem) {

presenter.eventCancel()

}

}

The Presenter

The role of the Router’s Presenter is similar to any other Presenter: to consume events sent by the ViewController

If the processing for an event only involves changing of a scene, the event will be sent right back to the ViewController.

func eventViewReady() {

output.showOnboardingFirstScene()

}

Here is an example of a Presenter forwarding a Cancel event to its Router:

class ItemEditPresenter {

...

func eventCancel() {

router.routeEditingCancelled()

}

}

The ViewController sends all events to the Presenter, even though the event may be sent right back, because the Presenter is responsible for making the decision of whether or not to send it back.

When the Router has to initialize data for its child scenes, or when the decision of which scene to display is dependent on state, the event is sent to the Router’s UseCase. As will be seen later, the Router’s Presenter can instantiate state data models that are injected into the Router’s child UseCases by their own Presenters.

Most of the Presenter’s responsibilities are about responding to its child VIP modules - see below.

The UseCase

It is not normally necessary for the Router to implement a UseCase, but there are two good reasons to implement a UseCase for a Router:

- to initialize data which will be shared by the UseCases of its children and

- to determine which scene should be displayed, based on state.

Here. the success or failure of a Save in a child is forwarded to its Presenter:

class ItemEditUseCase {

weak var output: ItemEditSaveUseCaseOutput!

...

func eventSave() {

...

entityGateway.itemManager.save( ... ) { result in

switch result {

case let .failure(error):

output.presentSaveError()

case let .success(item):

output.presentSaveCompleted()

}

}

}

}

The Presenter as UseCaseOutput

Whenever the Router implements a UseCase, the its Presenter will implement the UseCaseOutput.

In most cases the Router’s UseCaseOutput is pretty simple. It will perform localization and then forward the messages to its ViewController. The Presenter can also send messages to its Router.

Here the Presenter forwards the success event to its router, which will remove the scene. In the case of an error, the Presenter forwards the error event to its ViewController for display:

extension ItemEditPresenter: ItemEditSaveUseCaseOutput {

func presentSaveCompleted() {

router.routeSaveCompleted()

}

func presentSaveError() {

output.showSaveError(message: "There was a problem saving")

}

}

The ViewController as PresenterOutput

The job of the ViewController as PresenterOutput is to display the child scenes.

In a custom Router, the ViewController is responsible for initiating the display of the child ViewController by calling performSegue(withIdentifier:sender:). Here, the ViewController initiates a Segue to display an EditView:

private enum Segue: String {

case showDisplayView

case showEditView

}

func showViewReady() {

DispatchQueue.main.async {

self.performSegue(withIdentifier: Segue.showEditView.rawValue, sender: itemParameters)

}

}

The Router injects its Presenter into the childs Presenter. It also injects the domain parameters if there are any, into the presenter. In a custom ViewController, this is done in the prepare(for:sender:) override:

override func prepare(for segue: UIStoryboardSegue, sender: Any? = nil) {

switch Segue(rawValue: segue.identifier!)! {

case .showDisplayView:

let viewController = segue.destination as! ItemDisplayViewController

viewController.presenter.router = presenter

viewController.presenter.domainParameters = sender as! ItemParameters

case .showEditView:

let viewController = segue.destination as! ItemEditViewController

viewController.presenter.router = presenter

viewController.presenter.domainParameters = sender as! ItemParameters

}

}

It is usually easiest to pass domain parameters is via the sender parameter. If there is more than one, a struct or tuple should be used. This technique can be used even when not using VIPER, since the parameter is not used for any other purpose in a manual Segue.

The ViewController also has the option of displaying its own Views in lieu of displaying a whole ViewController. This might be the easiest way to display an error message when a failure is detected by the UseCase.

Subclasses of NavigationController

When the Router’s ViewController is a subclass of a Navigation- or SplitViewController, UI events generated by the segues are consumed by the controller. In this case, the respective -ControllerDelegate must be used to monitor the routing events.

The -ControllerDelegate.willShow method must inject the Router’s presenter into each child’s Presenter before the child is displayed.

extension TodoRootRouterNavController: UINavigationControllerDelegate {

func navigationController(_ navigationController: UINavigationController, willShow viewController: UIViewController, animated: Bool) {

switch viewController {

case let viewController as ItemRouterViewController:

viewController.presenter.router = presenter

case let viewController as ListViewController:

viewController.presenter.router = presenter

default:

fatalError("Unknown viewController encountered")

}

}

}

A Scene Change Example

Imagine a scenario where a ViewController displays a List and an Add Button. The user can choose to add a new item to the list or to display an item from the list.

When the Add button is tapped, a scene is displayed that allows the user to enter the details of a new item. When an item in the list is tapped, a scene is displayed that shows the details of the item.

It is the router’s responsibility to control the transition from the initial scene to the next scene. From the initial ViewControllers point of view, the router looks like this:

protocol ListRouter: class {

func routeDisplayItem(id: String)

func routeCreateItem()

}

It is the router’s responsibility to implement this interface.

The router is injected into to each child ViewController. It implements one routing protocol per child.

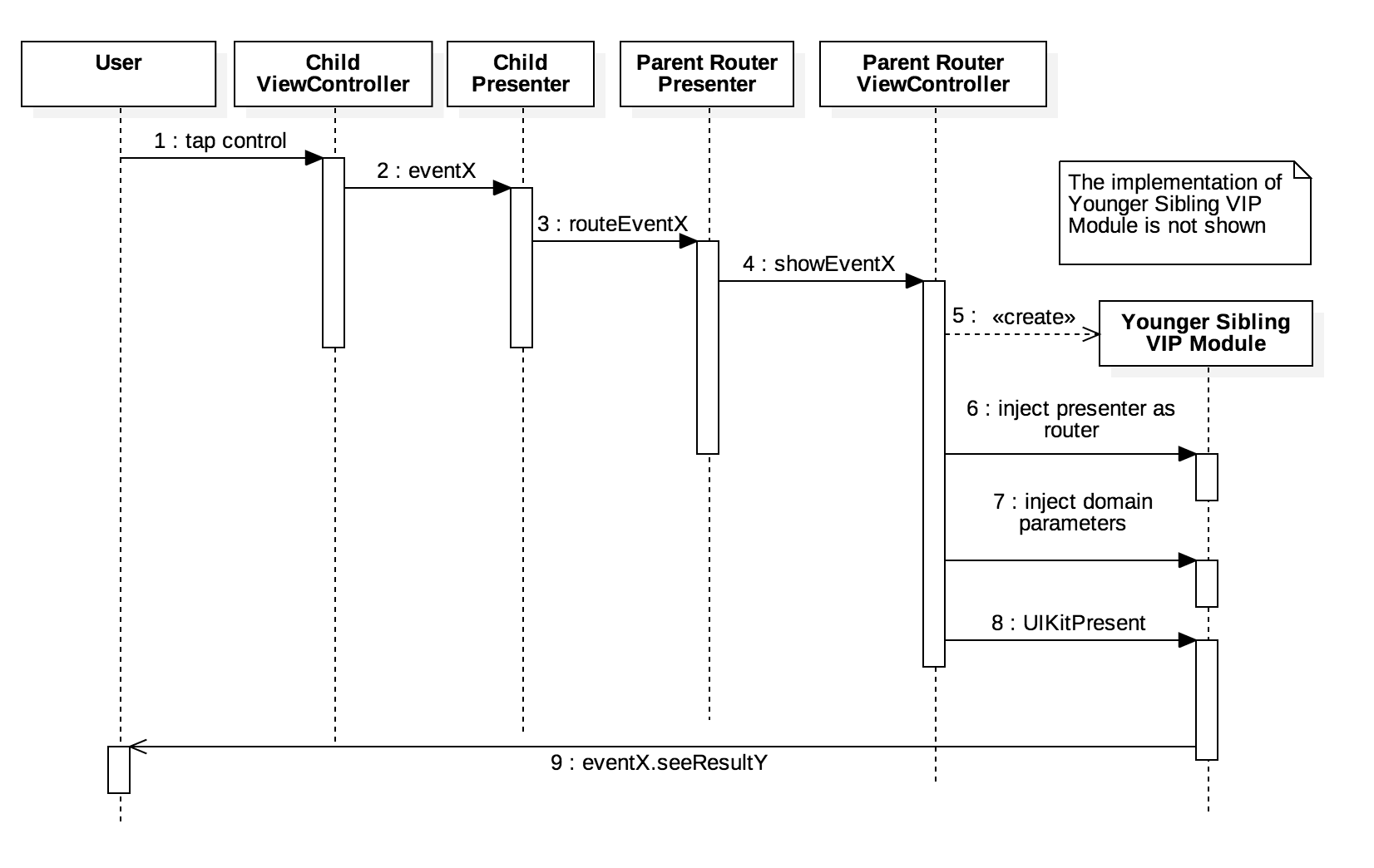

The following diagram shows a child ViewController initiating the display of an new scene:

The message sequence for the creation of a new scene is always the same, regardless of whether the router is derived from a NavigationController or a custom container ViewController.

The Child ViewController’s Role

The child ViewController receives events in the usual manner. The event is immediately passed on to the child’s Presenter. Here is the implementation for an Add button:

@IBAction func addTapped(_ sender: Any) {

presenter.eventCreateItem()

}

Here is the implementation for a TableViewCell selection:

extension ListAdapter: UITableViewDelegate {

func tableView(_ tableView: UITableView, didSelectRowAt indexPath: IndexPath) {

presenter.eventItemSelected(index: indexPath.row)

}

}

The Child Presenter’s Role

The Presenter sends the events on to the router as follows:

func eventCreateItem() {

router.routeCreateItem()

}

func eventItemSelected(index: Int) {

router.routeDisplayItem(id: viewModelList[index].id)

}

In the case of the item selection, the index is translated into the id of the item that will be displayed. The id was stored in the view model specifically for this purpose.

The Router Presenter’s Role

The job of the Router’s Presenter is simple - send the event on to the ViewController:

extension RootRouterPresenter: ListRouter {

weak var output: RootRouterPresenterOutput!

func routeDisplayItem(id: String) {

output.showItem(id: id)

}

func routeCreateItem() {

output.showCreateItem()

}

}

The Router ViewController’s Role

The Router’s ViewController initiates the Segues of its children by calling performSegue(withIdentifier:sender:).

In the example below, the Router ViewController is inherited from a NavigationController.

In the case of displaying the selected item, it transmits the id by capturing it in a closure, and then injecting the closure.

private enum RootRouterSegue: String {

case create

case show

}

extension RootRouterNavController: RootRouterListPresenterOutput {

func showCreateItem() {

let listViewController = viewControllers.first as! ListViewController

listViewController.performSegue(withIdentifier: RootRouterSegue.create.rawValue,

sender: nil)

}

func showItem(id: String) {

let listViewController = viewControllers.first as! ListViewController

listViewController.prepareFor = { segue in

let viewController = segue.destination as! ItemDisplayViewController

viewController.id = id

}

listViewController.performSegue(withIdentifier: RootRouterSegue.show.rawValue,

sender: nil)

}

}

Below, the closure is executed in the prepare(for segue:sender:? override. This may seem like its quite indirect, but the point is to decouple the child viewControllers while still making use of Segues.

class ListViewController {

var prepareFor: PrepareForSegueClosure?

...

override func prepare(for segue: UIStoryboardSegue, sender: Any?) {

if let prepareFor = prepareFor {

prepareFor(segue)

}

}

}

If you really wanted to be pure about responsibility, you could create a custom Segue whose source would be the NavigationController - it would not look as familiar in the storyboard, but it would make more sense from a responsibility point of view and would allow the Segue to be called directly from the NavigationController.

Transferring Data between Scenes

The router is mostly responsible for moving data between scenes. We can divide transferring data between scenes into 3 scenarios:

- transient data that a Scene must pass forward to another Scene,

- transient data that a Scene must pass backward to another Scene, and

- persistent data (state) that is shared amongst many Scenes.

Transferring Data to the Next Scene

Normally, using UIKit, when a ViewController instantiates another ViewController, data is passed forward to the new ViewController by injection. In VIPER, a Router instantiates a ViewController, so the Router must perform the injection. Data is first passed from the initial Scene to the Router.

Data sent to a Router should be translated by the Scene’s Presenter. A typical example of this, as seen above, is when a selection is made in a TableView and the index is translated by to an id before being passed to the Router.

Data that is captured by a UseCase should not be passed this way - it should be passed as described in the next section.

Transferring Data Shared Amongst Many Scenes

Recall that, in VIPER, Entities are never stored in a ViewController because they are never passed as output to the ViewController. The ViewController only knows about ViewModels.

It is common for multiple scenes to collaborate in order to complete a business Use Case.

Shared Entities that multiple UseCases manipulate should not be retrieved from the UseCase by the Presenter and then passed on to the Router, only to be passed to the next ViewController, Presenter and UseCase. This would be quite tedious and is against the rule that the ViewController should not know about Entities.

Injecting a Local State Model

In order to limit the scope of a State Model to a small number of scenes and allow for recursion the Router’s UseCase should instantiate a specific State Model to be used by itself and its child UseCases. The Router’s UseCase associates the Model with a UseCaseStore. The State is dissociated from the UseCaseStore when the Router’s UseCase is terminated.

In the simple case, where only one instance of a scene flow is presented, the State Model is set by assignment. In the case where the scene flow can be presented recursively, the newly created State model should be pushed onto a stack associated with the UseCaseStore. The stack is popped when the Router is destroyed. The scenes access the State by looking at the top of the stack.

Using this technique, the model’s scope is limited to just those scenes that actually need to access it.

Here is an example of a UseCase state model for a multi-scene business use case for sending money:

class SendMoneyUseCaseState {

var fromAccount: Account

var amount: Money

var recipient: Recipient

}

Below, the Router’s UseCase instantiates the model and associates it with the UseCaseStore :

class SendMoneyRouterUseCase {

// ...

private var useCaseStore: UseCaseStore

private var sendMoneyState = SendMoneyUseCaseState()

init(entityGateway: EntityGateway = EntityGatewayFactory.entityGateway,

useCaseStore: UseCaseStore = RealUseCaseStore.store) {

self.entityGateway = entityGateway

self.useCaseStore = useCaseStore

self.useCaseStore[sendMoneyStateKey] = sendMoneyState

}

// ...

}

Here a child scene’s UseCase injects the state into a Transformer:

class SendMoneyStepOneUseCase {

// ...

private let sendMoneyState: SendMoneyUseCaseState

init( entityGateway: EntityGateway = EntityGatewayFactory.entityGateway,

useCaseStore: UseCaseStore = RealUseCaseStore.store ) {

self.entityGateway = entityGateway

self.itemState = useCaseStore[sendMoneyStateKey] as! SendMoneyUseCaseState

func eventViewReady() {

let transformer = SendMoneySceneOneViewReadyUseCaseTransformer(state: sendMoneyState)

transformer.transform(output: output)

}

// ...

}

Here the state is disassociated from the EntityGateway:

deinit {

useCaseStore[sendMoneyStateKey].sendMoneyState = nil

}

If the state does not need to be initialized by the Router’s UseCase, there is probably no reason for the Router to have a UseCase.

Transferring Data Back to the Previous Scene

Often, a result that is captured in a UseCase must be passed back to a presenting Scene. Before the presented Scene is dismissed, the data can be sent back to the presenting Scene’s Presenter via a closure.

In the following example, the Presenter calls its Router to display an item. It passes the item’s id and a closure to execute if the user edits the item. A nice result of this implementation is that the index is captured by the closure, so there is no need to store it in a property:

func eventItemSelected(index: Int) {

router.routeDisplayItem(id: viewModelList[index].id) { [weak self] model in

if let strongSelf = self {

strongSelf.viewModelList[index] = ListViewModel(model: model)

strongSelf.output.showChanged(index: index)

}

}

}

The UseCase responds to the Back navigation event by calling the presentChanged method, but only if the item changed:

class ItemUseCase {

...

func eventBack() {

if state.itemChanged {

output.presentChanged(item: ListPresentationModel(entity: state.currentItem!))

}

}

}

Here is the code that calls the closure. Notice that the item being passed back is a ListPresentationModel, even though it was created from an item.

extension ItemPresenter: ItemBackUseCaseOutput {

func presentChanged(item: ListPresentationModel) {

switch startMode! {

case let .update(_, changedCompletion):

changedCompletion(item)

case let .create(addedCompletion):

addedCompletion(item)

}

}

}

Summary

In the VIPER architecture, a parent ViewController is responsible for the management of its child ViewControllers. Router classes are simply ViewControllers that instantiate and manage child ViewControllers. Unlike the UIKit architecture, all code related to routing is placed in the parent, not in the child.

The benefits of using a Router are:

- there is less code in each child ViewController

- each ViewController is decoupled from its parent and sibling ViewControllers, allowing it to be reused in multiple contexts, and

- the router is responsible for injection of data when it is not otherwise injected into the UseCase, so the resulting VIP modules are easy to test