Solving a Complex UITableView using Swift

Introduction

In this article we will discuss a technique for solving a complex UITableView. By complex, I mean a tableView that will display many more row types than exist in the source data set - in this case seven. At the same time, we will discuss a simple technique to reduce the size of the UIViewController that owns the tableView.

Dynamic Display

It is not unusual to have to create a UITableView that displays more than one kind of row. Maybe the rows are alternately coloured and there is a refresh button or a total at the end of the table. Maybe in one state, a cell has a particular arrangement of views, but in another state, it has another arrangement.

This kind of tableview can be created easily using the cell index to access the item in the source data set. This index is given via cellForRowAt. For example, when cellForRowAt is called, we can determine:

- the cell colour from the index position,

- when to display the refresh button cell or total cell, instead of a regular cell, based on the size of the dataset,

- the cell type with a particular view arrangement based the source data item,

- the total from the all items in the dataset,

- the data to display for the current row.

The first three items are concerned with configuration and the others are concerned with assignment of data to the views. Configuration and assignment should be the only responsibilities of cellForRowAt.

A cellForRowAt method that implements all of the above responsibilities dynamically will contain many ifs, switches, &&s and nested ifs, most of which are required just to determine the type of the cell. Once the type of the cell is known, it is easy to do the configuration and make the assignments.

The code in cellForRowAt is referred to as dynamic because the cell type must be determined and then processed each time that cellForRowAt is called. This is in contrast to a static technique, where the cell type is predetermined and the cell processing is done once, before cellForRowAt is ever called.

When the assignment code is entangled in the code responsible for determination of type, it becomes very hard to understand and change. Whenever I write or see code like this, I know there are hidden classes just begging to be found.

Over time, when new requirements emerge, the code will have to be changed. Unless this entangled code is refactored so that it is extensible and understandable, changes made by various developers will further obscure its intent.

UITableView Sections

Occasionally, a more complicated requirement comes along, such as having to create a UITableView that displays many kinds of cells, where the cells repeat in regular cycles.

An example of this would be a report that has repeating groups, where each group consists of a Header, followed by a repetition of Detail Rows, followed by a Footer. The Header might display a date, location or type; maybe it contains a button. The Footer might display a total for the section. The Details display the remaining data from the input dataset. There may be more than one kind of Detail - some might display a button and some might not.

One solution for this kind of requirement is to use UITableView sections. Tableview sections directly support the display of section header and footer views. The tableView can use indexPaths containing a section index and a row index to access each section and each section’s associated data.

When using sections we have to organize the input data into groups to represent the sections. Sometimes, by chance, the input data is already structured into groups, but, most of the time we have to organize it. Usually the structure will be an array of structures containing precalculated header and footer data and an array containing the related portion of the input dataset.

A Complex Requirement

Things get more complicated when we have to produce a display containing repeating groups that themselves contain repeating groups. The reason It is more complicated it that UITableViews do not directly support this kind of structure.

Suppose there are two simple input streams of credit card transactions: one Posted, and the other Authorized. Posted Transactions are those that are due for payment; Authorized Transactions are those that are recent and not due. The input data streams are not identical in format, but each one contains identical data. Each transaction record consists of a Date, a Description, an Amount, and a Debit indicator. The input streams are sorted by Date.

The requirement is to create a display where the Transactions will be displayed in two groups. Posted Transactions will be displayed first, followed by Authorized Transactions. The Transaction type, Posted or Authorized will be displayed as a Header at the beginning each group. The total of each Transaction Group will be displayed as a Footer at the end of each group. Transaction rows will be further grouped and displayed by Date.

The Date will be displayed in a Subheader before each group of Details having the same date. Each Date group and Total row will to be banded with alternating colours. There is also a requirement that the margin before the Date SubHeader is the same as the margin after the last Detail in each row - imagine a box containing the Date followed by the Details with equal top and bottom margins.

Each Detail row will contain the Description, and Amount of the Transaction. Debit Amounts will be displayed with negative signs.

The last row will contain the total of all of the displayed transactions.

When data is not available for any of the transaction streams, we are required to display the Header as usual with an error message, without Subheaders, Subfooters or a Footer.

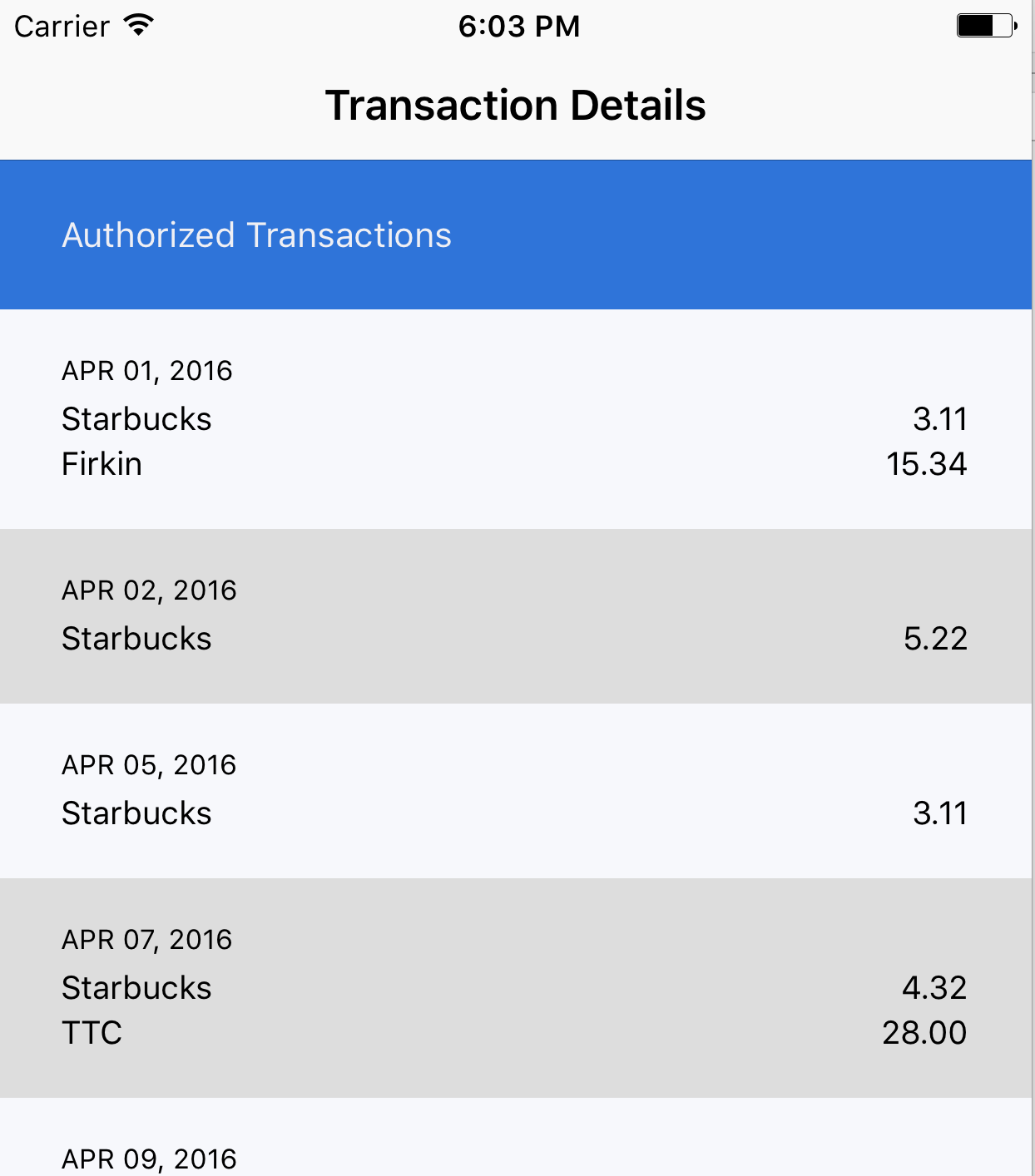

Here are screen shots of what the display should look like. Here is the top:

Here is the middle :

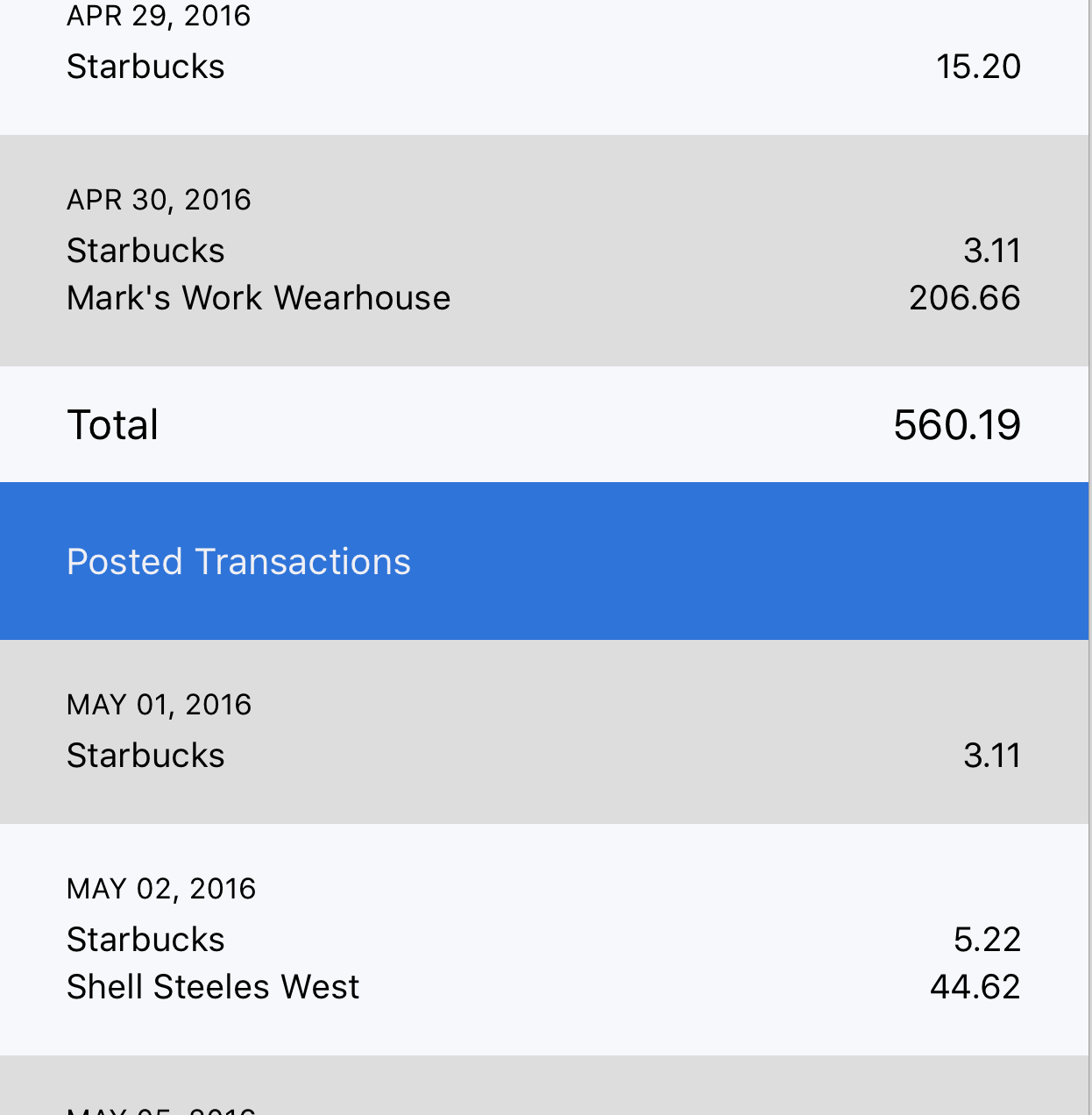

And here is the bottom:

As you can see, the output has repetitions of Transaction Type Groups and each of those has repetitions of Date groups. We cannot directly map the original data set, simply by an index, to the data to be displayed. There are more rows in the display than in the original data streams.

We cannot rely on a function of the index to determine the cell type for a given index and we cannot rely on the builtin section support, because we have to implement section Headers, Subheaders, Subfooters and Footers.

When things get this complex, a different kind of solution is necessary.

A Different Perspective

One way to think about the task is this: transform the input data stream to an output stream and then print it on paper, or at least on a web page, of whatever length is required. The trick is to not commit to the actual output styling - its just an abstraction. Once the output data stream has been created, it just has to be collected in such a way that the tableView can easily display the output.

This technique is demonstrated in a demo app that you can find at ReportTableAdapterDemo.

In order to satisfy the requirements for the demo, we can break down the app into a number of tasks

- represent the the input data for the demo

- visualize the output stream data

- transform the transaction rows into a form that can be easily displayed

- display the rows in a tableview through a datasource

The Data

First, we have to organize the data for the demo.

In the demonstration code each transaction is represented like this:

struct TransactionModel {

let group: String

let date: String;

let description: String

let amount: String

let debit: String

}

The TransactionModel represents the data model that a service layer would deliver to the viewController. The data is not delivered exactly as it should be - we will revisit this in the next post. It does not matter that the data is coming from two different sources. What matters is that the data can be coerced to the same format, which allows the processing for the two sources to be identical - think: protocols.

The data represents the two input streams: authorizedData and postedData. Both streams are simply arrays of TransactionModels. Each transaction looks similar to this:

TransactionModel( group: "P",

date: "2016-05-01", description: "The Rex", amount: "3.11", debit: "D" )

You can view the whole input stream here.

Designing the View

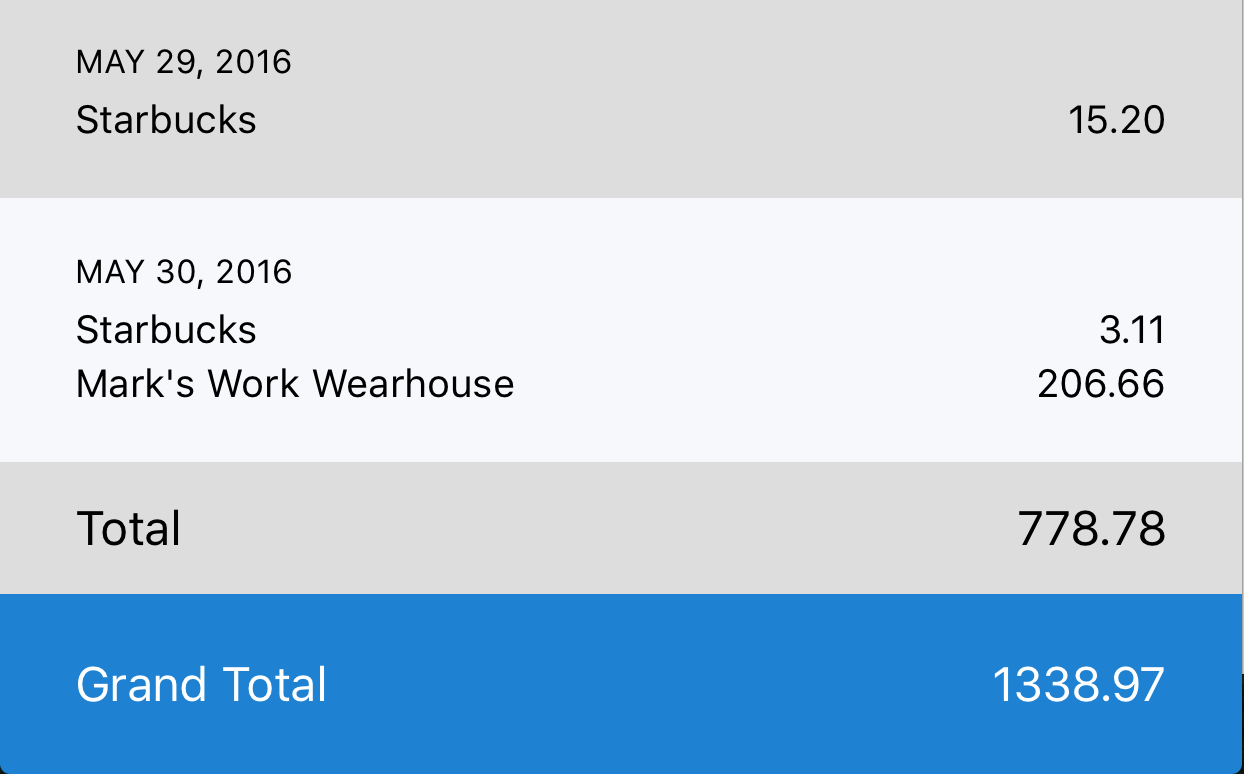

Next, we want to design the rows we are going to “print”. First we visually design with IB and then think about the code to generate the lines.

We specify a cell to represent each type of row that can be displayed. There are 7 cell types, corresponding to:

- header,

- subheader,

- details,

- subfooter,

- footer,

- message, and

- grandfooter

Here is a snapshot of the cell layouts in IB:

The purpose of each cell type is should be obvious with respect to the screen shots above.

Notice 2 subtleties: the footer and the grandfooter look similar; and each Date group is displayed as a block in one colour, where the top and bottom margins are equal

Part of the solution strategy is to avoid computation wherever it is possible to use structures instead. Even though the footer and grandfooter rows look similar, we use a separate cell type for each because they behave differently in the following ways:

- The background colour of the footer cell is determined dynamically based on its row position (odd or even).

- The grandfooter cell background is always blue.

- The static title text is different

By separating out the behaviour by type, it will be easy to change either of the two row styles, without affecting the other, when a design change is required.

In the same way, the detail cell could have been designed so that it would change its height dynamically, depending on whether it was the last row in a group. We would have to introduce a boolean to explicitly record the actual type that the cell should be. Instead of this, a subfooter cell is introduced just to take up the space below the last detail. It is highlighted in the screen shot above.

Generating the Rows

As mentioned earlier, the strategy is to transform the input stream into an output stream. The output stream can then be displayed by the tableview.

Since each section is identical in format, we only have to write a transformer for one input data stream. We can reuse the transformer for the second data stream.

The TransactionListTransformerOutput protocol supports the notion that we could be sending the output to anywhere. It is shown here:

protocol TransactionListTransformerOutput {

func appendHeader(title: String)

func appendSubheader(date: String )

func appendDetail(description: String, amount: String)

func appendSubfooter()

func appendFooter(total: String)

func appendGrandFooter(grandTotal: String)

func appendMessage(message: String)

}

Each method in the protocol represents a row type of the output. The protocol’s name derives from the fact that it represents the output of the transformation of the TransactionList.

The transformer, called from viewDidLoad is a follows:

private func transformFromTwoSources() {

appendSection(transactions: authorizedData, title: "Authorized")

appendSection(transactions: postedData, title: "Posted")

adapter.appendGrandFooter( grandTotal: String(grandTotal) )

}

appendSection is implemented as follows:

private func appendSection(transactions: [TransactionModel]?, title: String) {

adapter.appendHeader( title: "\(title) Transactions" )

if let transactions = transactions {

var i = 0

var transaction = next(transactions: transactions, i: &i )

var total = 0.0

while transaction != nil {

let curDate = transaction!.date

adapter.appendSubheader(date: curDate)

while transaction != nil && transaction!.date == curDate {

var amount: String

if (transaction!.debit != "D") {

amount = "-" + transaction!.amount

}

else {

amount = transaction!.amount

}

total += Double(amount)!

adapter.appendDetail(description: transaction!.description, amount: amount )

transaction = next(transactions: transactions, i: &i )

}

adapter.appendSubfooter()

}

adapter.appendFooter(total: String(total) )

grandTotal += total

}

else {

adapter.appendMessage(message: "\(title) Transactions are not currently available. You might want to call us and tell us what you think of that!")

}

}

appendSection transforms the input TransactionModels to an output stream defined by the TransactionListTransformerOutput protocol. Given the requirement that the input streams come from two different sources, a TransactionModel could also be implemented as an abstract protocol, representing two different concrete models.

The transformer assumes that the transactions are sorted by date. The code is organized so that

- the input is a stream of transactions terminated by

nil - there is an iteration for each Date.

- within the Date iteration there is an iteration for each Detail that has the same date.

- at the appropriate times, rows are appended to the output stream

The first point is implemented by this idiom:

private func next(transactions: [TransactionModel], i: inout Int ) ->TransactionModel? {

let transaction = ( i < transactions.count ) ? transactions[ i ] : nil

i += 1

return transaction

}

At the beginning of each date iteration, the current date is set from the transaction date of the first record in the group. The rest of the code in this block represents the current date group. All rows for this group, including the Subheader, Details and Subfooter, will be the same band colour. If we were required to print the subtotal for the date, we could easily set-up a date total in this block; setting it to zero at the top of the loop.

In the inner iteration the data is transformed and added to the section total. As soon this processing is complete, the next transaction is retrieved.

Data is sent to the output stream as it is produced.

By the way, the structure for the transformer was derived systematically from the output requirement using a technique called Data directed Design, which will be discussed in a future article.

The TableView Adapter

From the break down of the tasks listed above, it seems like we need (at least) two major classes: one to transform the input data stream and one to supply the output of the transformation to the tableView as a dataSource.

Massive View Controllers

There is a lot of talk these days about the problems associated with the Massive ViewController (MVC). The problem with MVCs is that they are hard to understand because of large scope and they are hard to change due to coupling.

One simple-to-implement best practice, which will allow us to avoid MVCs that contain a tableView is to create a separate class to act as the datasource for a tableView. Almost every demonstration, by Apple or otherwise, implements the dataSource as part of the viewController. Once you get used to separating them, you will see that implementing a dataSource in a ViewController is an anti-pattern leading to code bloat. You can read more about this in Lighter View Controllers.

By moving the the task of collecting the TransformerOutput to another class, called the Adapter, we neatly split the application into two major components. The viewController generates the rows and the adapter collects the rows.

Both the ViewController and the Adapter have other responsibilities. The ViewController is also responsible for managing its views and the adapter is responsible for producing cells for the table in its role as a TableViewDataSource. That being said, separating out the Adapter from the ViewController is a good start to separating responsibilities. The resolution of the other conflicting responsibilities is left to a future article.

Three Protocols

The adapter implements three protocols: UITableViewDataSource, UITableViewDelegate and TransactionListTransformerOutput . Each protocol has been implemented as an extension. This is a great practice because it reduces the scope of the protocol implementations and allows the compiler to accurately place messages about missing implementations .

The only thing that the extensions do not implement is the data and this is left to the class.

class TransactionListAdapter: NSObject {

fileprivate var rowList = [Row]()

fileprivate var odd = false

}

The TransformerOutput Implementation

Although the TransactionListTransformerOutput protocol describes the output of the Transformer, it also describes the input to the Adapter. The naming scheme suggests that the rows will be appended to the output. The response to each message of the protocol is to append a row to the rowList.

extension TransactionListAdapter: TransactionListTransformerOutput {

func appendHeader(title: String ) {

rowList.append( HeaderRow( title: title ) )

}

private static let inboundDateFormat = DateFormatter.dateFormatter( format: "yyyy'-'MM'-'dd" )

private static let outboundDateFormat =

DateFormatter.dateFormatter( format: "MMM' 'dd', 'yyyy" )

func appendSubheader(date inboundDate: String) {

odd = !odd

let date = TransactionListAdapter.inboundDateFormat.date( from: inboundDate)!

let dateString = TransactionListAdapter.outboundDateFormat

.string(from: date ).uppercased()

rowList.append( SubheaderRow( title: dateString, odd: odd ) )

}

func appendDetail( description: String, amount: String ) {

rowList.append( DetailRow( description: description, amount: amount, odd: odd ) )

}

func appendSubfooter() {

rowList.append(SubfooterRow( odd: odd ))

}

func appendFooter(total: String) {

odd = !odd

rowList.append(FooterRow(total: total, odd: odd))

}

func appendGrandFooter(grandTotal: String) {

rowList.append(GrandFooterRow(grandTotal: grandTotal))

}

func appendMessage(message: String) {

rowList.append(MessageRow(message: message))

}

}

The append methods are converting the data into Rows. the data in each row is in a format that will be used directly for display. By the time all of the rows are generated, there are no decisions left to be made with respect to height, colour, view configuration and data display content. The data retained in the Rows will be assigned directly to the Controls in the Cells.

The band colour has been captured by the odd property of the row. The actual colour code could have been stored in each row, but colour specification is a best confined to the view, so odd is used as a proxy.

Storage of the Rows

The Rows are implemented as structs. Less code is required to implement the Rows using structs than classes, mostly because constructors do not have to be specified. Using let, they are also immutable.

In the future, for testing, we will want to compare the rows and Swift directly supports equality comparison of structs (of scalars).

Each row type implements the Row protocol.

private protocol Row {

var cellId: CellId { get }

var height: CGFloat { get }

}

The cellId property and associated enum are used to generate the identifier used by dequeueReusableCell(withIdentifier:). The height property is the height of the cell to be returned by tableView(_:heightForRowAt:).

private enum CellId: String {

case header

case subheader

case detail

case subfooter

case footer

case grandfooter

case message

}

The row types are implemented as follows:

private struct HeaderRow: Row {

let title: String

let cellId: CellId = .header

let height: CGFloat = 60.0

}

private struct SubheaderRow: Row {

let title: String

let odd: Bool

let cellId: CellId = .subheader

let height: CGFloat = 34.0

}

private struct DetailRow: Row {

let description: String

let amount: String

let odd: Bool

let cellId: CellId = .detail

let height: CGFloat = 18.0

}

private struct SubfooterRow: Row {

let odd: Bool

let cellId: CellId = .subfooter

let height: CGFloat = 18.0

}

private struct FooterRow: Row {

let total: String

let odd: Bool

let cellId: CellId = .footer

let height: CGFloat = 44.0

}

private struct GrandFooterRow: Row {

let grandTotal: String

let cellId: CellId = .grandfooter

let height: CGFloat = 60.0

}

private struct MessageRow: Row {

let message: String

let cellId: CellId = .message

let height: CGFloat = 100.0

}

The Rows are pretty simple. They contain precisely the data needed for display; no further conversions are necessary. The result is that the Rows are pure immutable ViewModels, having no behaviour.

Where to perform data conversion is interesting because there are many choices of where to place it: in the cell binding function, in the initializer for the ViewModel, in the transformer output function (the appender), or in the transformer itself. For now, most of the conversions have been placed in either the transformer or in the transformer output, but I think there is a better placement strategy. We will discuss this choice again in the next post.

The Cells

As discussed, the second major responsibility of cellForRowAt is to assign values to the views. The TransactionCell protocol specifies the interface to bind the data in a Row to a Cell for display. Each Cell must implement bind(row:).

The Row banding colour is a behaviour that is implemented by many of the cells. Since there are only two band colours, a boolean property called odd will be used to capture the banding colour of the cell with respect to the group position. This behaviour is supplied by setBackgroundColour(odd:).

private protocol TransactionCell {

func bind(row: Row)

}

private extension TransactionCell where Self: UITableViewCell {

func setBackgroundColour(odd: Bool) {

let backgroundRgb = odd ? 0xF7F8FC : 0xDDDDDD

backgroundColor = UIColor( rgb: backgroundRgb )

}

}

Protocol Extensions are a great place to put reusable methods that usually end up in a base class.

It would have been better to place the cell classes in the scope of the TransactionListAdapter or at least to make them private to the file, but Interface Builder does not seem to be able to find them in either of these situations, so we will use private IBOutlets.

There is not much left to do in the implementation of the bind methods - just cast, then set a few controls and the background colour.

class HeaderCell: UITableViewCell, TransactionCell {

@IBOutlet private var titleLabel: UILabel!

fileprivate func bind(row: Row) {

let headerRow = row as! HeaderRow

titleLabel.text = headerRow.title

}

}

class SubheaderCell: UITableViewCell, TransactionCell {

@IBOutlet private var titleLabel: UILabel!

fileprivate func bind(row: Row) {

let subheaderRow = row as! SubheaderRow

titleLabel.text = subheaderRow.title

setBackgroundColour(odd: subheaderRow.odd)

}

}

class DetailCell: UITableViewCell, TransactionCell {

@IBOutlet private var descriptionLabel: UILabel!

@IBOutlet private var amountLabel: UILabel!

fileprivate func bind(row: Row) {

let detailRow = row as! DetailRow

descriptionLabel.text = detailRow.description

amountLabel.text = detailRow.amount

setBackgroundColour(odd: detailRow.odd)

}

}

class SubfooterCell: UITableViewCell, TransactionCell {

fileprivate func bind(row: Row) {

let subFooterRow = row as! SubfooterRow

setBackgroundColour(odd: subFooterRow.odd)

}

}

class FooterCell: UITableViewCell, TransactionCell {

@IBOutlet private var totalLabel: UILabel!

fileprivate func bind(row: Row) {

let footerRow = row as! FooterRow

totalLabel.text = footerRow.total

setBackgroundColour(odd: footerRow.odd)

}

}

class GrandFooterCell: UITableViewCell, TransactionCell {

@IBOutlet private var totalLabel: UILabel!

fileprivate func bind(row: Row) {

let grandFooterRow = row as! GrandFooterRow

totalLabel.text = grandFooterRow.grandTotal

}

}

class MessageCell: UITableViewCell, TransactionCell {

@IBOutlet private var messageLabel: UILabel!

fileprivate func bind(row: Row) {

let messageRow = row as! MessageRow

messageLabel.text = messageRow.message

setBackgroundColour(odd: true)

}

}

The UITableViewDataSource Implementation

At last we can move on to the implementation of the UITableViewDataSource and UITableViewDelegate.

extension TransactionListAdapter: UITableViewDataSource {

func tableView(_ tableView: UITableView, cellForRowAt indexPath: IndexPath) -> UITableViewCell {

let row = rowList[indexPath.row]

let cell = tableView.dequeueReusableCell(withIdentifier: row.cellId.rawValue, for: indexPath)

(cell as! TransactionCell).bind(row: row )

return cell

}

func tableView(_ tableView: UITableView, numberOfRowsInSection section: Int) -> Int {

return rowList.count

}

}

extension TransactionListAdapter: UITableViewDelegate {

func tableView(_ tableView: UITableView, heightForRowAt indexPath: IndexPath) -> CGFloat {

return rowList[ indexPath.row ].height

}

}

As you can see, tableView(_:numberOfRowsInSection:) is trivial.

tableView(_:cellForRowAt:) is more interesting in that it is also fairly simple: just access the row, dequeue the cell for the row’s type (cellId), bind the row data to the cell and return the cell. How simple is that.

tableView(_:heightForRowAt:) simply returns the height given by the row.

It is interesting how trivial the implementation of tableView(_:cellForRowAt:) is. All of the usual work of deciding which cell is being setup is being handled automatically via polymorphism - no switch statements required. All of the usual control assignments are relegated to the Cell classes that own the controls.

The UITableViewDataSource knows only about TransactionCells. Each TransactionCell knows what kind of Row it can handle.

Summary

This solution, which involves generating rows to be consumed by a TableView adapter can be used whenever the data display requirement is non-trivial. I recommend using this kind of solution even when there is a one to one mapping of cells to input steam data. The if statements in a typical cellForRowAtIndex implementation are usually related to determination of type and the easiest way to simplify the code is to use structures to capture ViewModels which can be displayed directly by the Cells. This greatly simplifies the code by distributing the various concerns to smaller, more specific, classes.

We should avoid performing calculations to dynamically determine types, because calculations produce bugs. Structures are much easier to understand and their use does not provide an opportunity to produce bugs.

Imagine if all 3 protocols were implemented in the ViewController. All 325 lines of code would have resided in one file. It is easier to test that the Transformation is working correctly when classes are more specific in their responsibilities.

The Cells and Rows could have been moved into files of their own, except that the Rows would have to be internal scope, not private, because they are used by the Cells. It’s not that the internal scoping is an issue, it’s that the Row names are too general for the increased scope. Sometimes it’s just better to use better names to make things safe than to use private access. We will discuss this further, in the next blog article.

It is extremely easy to extend this pattern further with new cell and row types. I didn’t think twice about how to add the extra space in the banded block.

By the way, in Android, ListViews and RecyclerViews do not have builtin support for sections, so I use the kind of solution presented here even when the requirement is only for single repeating sections. In iOS, I never use UITableView section support unless I need to display floating headers - I find it easier to use the kind of solution presented here.

In the next instalment, we will look at how enums can be used to replace structs to simplify the code even further.